Through a connection from a Stanford classmate, I visited a school for disabled children and community programs in the slums. Once again, I realized how doubly difficult it is to be poor and disabled, physically or emotionally. Still, I was impressed by the competence and compassion of the school’s staff who insist that these children are treated with dignity and, ultimately, empowered to live a normal life.

I also met with a group of mothers from the slums. These women are part of a self-sustaining help group. With sewing machines, they produce goods such as tablecloths and handcrafts. As they work, they discuss the challenges they face as well as support each other.

I introduced myself to the group and explained my background. When I mentioned my work combating domestic violence, one woman raised her hand. She was a composed woman in her early twenties who was 7 months pregnant. She explained that her husband had died six months ago. He was killed by a train on the tracks near the slums. She was unsure whether it was an accident or murder. Such a death is not uncommon among Mumbai’s poor; accidents occur because tracks are often crossed or used as bathrooms. More tragically, the tracks are sometimes used as killing grounds (railroad deaths are difficult for the police to track, if they are interested in investigating at all).

On top of grieving, this woman had to deal with an abusive family. In accordance with tradition, she had moved in with her husband’s family after she got married. Since her husband’s death, her in-laws had been harassing her because they wanted to claim the small amount of compensation that the railroads provide for anyone who dies on the tracks. She was afraid for her life, especially after she gave birth. Her greatest fear was that she would have a male child and her in-laws would take the boy and kill her. With a male heir, there was no need for her.

As the group discussed her alternatives, I realized how few options this woman had. She desparately needed the compensation money but she also had to escape. She cannot go home as her family will not accept her. And there are no shelters. She could call the police but they are unlikely to respond. Instead, she will have to work with the group to establish an informal method of protection where she will rely on friends and neighbors to intervene if the abuse escalates. And she will just hope for a girl.

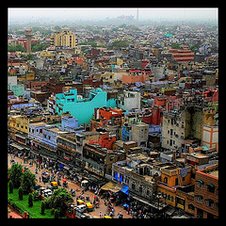

I felt incredibly humbled and saddened. I also learned that there is an entire informal system that operates in lieu of the formal structures in the slums. From basic services to courts and childcare, these slum communities function in parallel to the official world. Government-issued property deeds may not exist but there is a network of slum landlords who “own” all the property and collect rent every month. There are informal police (thugs) who ensure “safety and security” for a certain price. The moneylenders and merchants offer products, most of which are as expensive (or more) as those you find outside of the slums. Yet again, location is everything. In fact, some research indicates that it may be costlier in relative terms to live in the slums. People spend more of their incomes on basic services and goods because they have such limited options.

[Post-script: I will email the community program staff to find out what has happened with the woman I met and will update the blog if I find out more.]

No comments:

Post a Comment